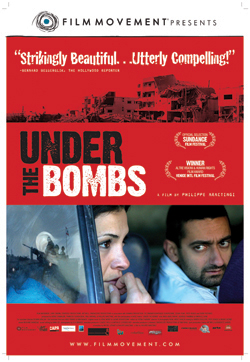

As part of the Global Understanding Convention, the final film in this year’s Provost Film Series, Under the Bombs, was screened on April 5 in Pollak Theatre.

The evening included speakers Thomas Pearson, Provost and Vice President of Academic Affairs, Azzam Elayan, professor of chemistry, and Saliba Sarsar, professor of political science.

The movie was set during Israel’s brief but devastating attack against Lebanon during 2006. Here, hundreds of air raids, as well as other bombings, took place, killing thousands of civilians. This film focused on the fictional narrative of one woman, named Zeina Nasrueddi (Nada Abou Farhat), as she attempted to find her sister Maha and son Karim.

Pearson was very concerned with the social and political issues that created the situation in Lebanon. “I chose the film Under the Bombs because of the issues involving Christians and Muslims in the Middle East. I wanted a film reflecting those cultural interactions and collisions.”

It is difficult to find a movie that is simultaneously enjoyable and enlightening. Films like Under the Bombs, which are sometimes called docu-dramas for combining elements of fiction and documentaries, can have difficulty being judged as a quality movie because either the fiction doesn’t always blend well with the drama or such a film is written with too much focus on the documentary, leaving the fiction bland and tasteless. The viewer of a docudrama may often think the film is boring or “tolerable at best.”

Let me put this in the most direct manner possible: Under the Bombs was fantastic.

Foremost, director Philippe Aractingi was both adventurous and extremely intelligent. He brought attention to the war and invoked the viewer’s empathy by showing scenes of actual bombings, refugee stations, wounded or dying people and the raw carnage of Lebanon. Having ventured out into the war zone to capture such footage, he put his life at risk to capture the real attacks against his people.

This footage was incorporated during the entire film, showing the audience that the presence of the military was a constant reminder that Zeida and her taxi driver, Tony (George Khabbaz), could be killed at any moment. The director later had Farhat as Zeida speak with tourists and journalists as though her son was real. Many of the people she spoke to were never informed that the child did not exist, so their reactions were completely genuine. Everything from what those people said to the pain in their facial expression was improvised and real.

This brings up another point as the acting was so great that at times I forgot that what I was watching was primarily fiction. Farhat played the panic-stricken mother so well that the viewers were on the edge of their seat from the beginning of the movie. Halfway through the movie, she receives tragic news and bursts into tears, overwhelmed by grief. Her voice, face and mannerisms were so accurate that it was difficult to believe it was just acting.

Khabbaz, who plays Tony, was equally believable, though he played a polar opposite. The charismatic cabdriver convinced the audience to fall in love with the antics he went through to prevent Zieda from breaking down or losing hope.

As the movie progressed, it became clear that his humorous demeanor was meant to mask his own fears and doubts. While he originally regarded Zieda as little more than another customer, he came to identify with her through these shared vulnerabilities, sacrificing his time and money to aid her.

As the movie progressed, it became clear that his humorous demeanor was meant to mask his own fears and doubts. While he originally regarded Zieda as little more than another customer, he came to identify with her through these shared vulnerabilities, sacrificing his time and money to aid her.

The acting was superb and the directing was top-notch, but the best part was how well Under the Bombs captured the fear, pain and adversity the Lebanese were subjected to during this attack. Empathy overwhelmed the viewers as the camera showed real children crying for their parents during the air raids. As bombs leveled schools and tore open homes, one can’t help but think, “That could’ve been my home.” While, of course, we do not live in Lebanon, the message is clear: The homes there function like homes in America do; the schools educate as ours do; the people scream, cry and suffer like we do.

This point lingers throughout the movie. As the camera looks over ruined buildings, burning signs and hundreds of deceased or displaced citizens, the viewer comes to realize whether in war or peace we are all alike.

Rather than show aspects of Lebanese culture or society, it shows the nature of fear, using the viewer’s inherent desire for peace and safety to allow us to identify with the Lebanese society.

Under the Bombs was one of the most enlightening and poignant cinematic experiences of my life. The juxtaposition of the quest to find a missing child against the absolute carnage of war created an incredibly moving film.

The screening ended with a question and answer session with Sarsar and Elayan. They took the time to point out the potential for violence that future wards could bring and how this film is just one example of why we must strive for peace. “What we saw is Sunday school compared to what will happen if Israel were to attack Iran,” said Sarsar.

The last thing by Elayan, as well as the last thing said during the presentation, was also the most powerful. “I hope all conflicts are someday resolved by the power of reason rather than for the reason of power.”

IMAGE TAKEN from filmmovement.com