The Monmouth University School of Humanities and Social Sciences held a panel discussion on the wrongful convictions of Rubin “Hurricane” Carter and John Artis on Friday, Sept. 17.

The event took place over Zoom and featured panelists John Artis, H. Lee Sarokin, Lesra Martin, Vanessa Potkin, and moderator Raymond M. Brown.

“All institutions of higher education that receive federal funding are charged with holding an event on Sept. 17, Constitution Day, highlighting the Constitution,” explained Thomas Veit, Interim Dean of the Wayne D. Murray School of Humanities and Social Sciences. “Today, we’ve put together an incredible panel to talk about the Constitution and its implications.”

“Those of you who have tuned in now for the next 90 minutes are in for an intellectual, cultural, and historical feast that surrounds the Constitution and many of the issues that flow from it in a very vital way,” said moderator Raymond M. Brown, Esquire. “You have four of the finest minds in the country to talk about questions of justice in a meaningful way, having each learned it in their own way from a different perspective.”

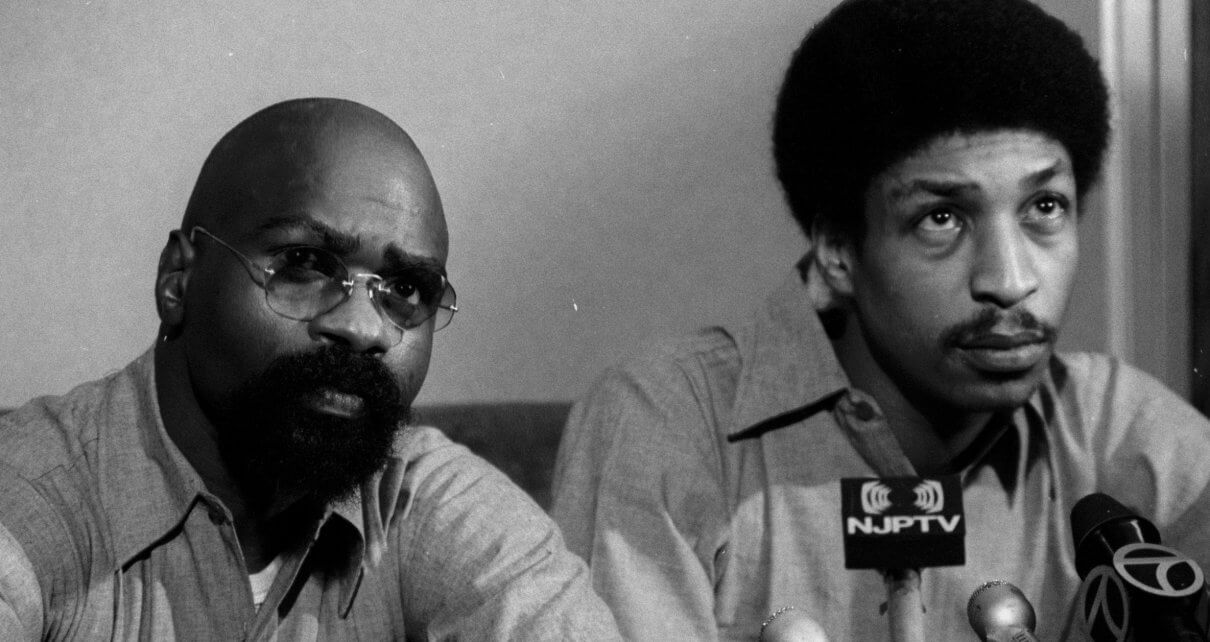

The case, described in an email sent to University students, dealt with the wrongful conviction of professional boxer Rubin “Hurricane” Carter and John Artis following a shooting in a tavern in Patterson, NJ that resulted in the death of a bartender and two patrons. Both men were charged with murder and sentenced to life in prison in 1967, only to be retired and reconvicted again in 1976. It wasn’t until 1985, 22 years later, that United States District Court Judge H. Lee Sarokin reversed the convictions on constitutional grounds and all accusations were dismissed.

During the second trial, the prosecution argued that race played a role in the murders because the victims were white and Carter and Artis were black. “The argument was made that it was typical that black men would go out and shoot somebody they didn’t know, and that was basically what I relied on in granting the writ of habeas corpus because I thought that the argument was so outrageous,” said Sarokin. “It was attributed to an entire group and wasn’t focused at all on Carter.”

“After you get over the fear of being arrested and on trial for a crime you didn’t commit, and as less evidence begins to filter through the courtroom, you get extremely angry,” said John Artis. “I’m on trial for my life for doing nothing. You realize exactly how vulnerable and helpless you are when you’re sitting in a courtroom of that nature.”

Race was a large topic of discussion during the panel. “You can never make the mistake of separating social justice issues from criminal justice issues because quite often, they go hand in hand. You have to look at the context of the history that was going on across the US and put that in the context of the mindset of the jury at the time,” explained Lesra Martin, Esquire, who studied the case as a teenager and helped win Carter’s release from prison and eventual exoneration.

Aside from the prosecution’s reliance on race in their argument for the second trial, racial disparities were also apparent in the jury selection process. “An issue came up where a black woman only had a 4th grade education and a white gentleman had a 3rd grade education,” said Artis. “Only she was released for cause because the judge felt that she wouldn’t be able to handle all of the technical language that would be present in a courtroom. He permitted the white gentleman to remain on the jury who slept through most of the trial anyway.”

When asked whether he believes that there’s a presumption of innocence in the courtroom, Artis responded “No, there isn’t. The belief is if you were innocent you wouldn’t be sitting at the defense table. There’s a presumption that people of color are more prone to commit violent crimes than any other race.”

Sarokin went on to describe the efforts that judges make to maintain a presumption of innocence in their courtroom. “We do everything we can to negate those opposite forces. It used to be that the defendants were brought into the court from prison in their jumpsuits, sometimes in shackles. We’ve tried everything we can to minimize the opposite forces at work and remind the juror’s of the fact that there is a presumption of innocence.”

Still, race continues to play a large role in many wrongful convictions. Vanessa Potkin, Esquire and attorney for the Innocence Project went on to explain how problems involving race in the justice system are far from over. “In terms of exonerations and race, when you take into account DNA and non-DNA exonerations to date, since 1989 there have been 2,858 cases documented of wrongful conviction. Half of those cases of those who were wrongfully convicted were black. The racial disparities play out in the numbers. You’re seven times more likely to be wrongfully convicted of murder if you’re black than if you’re white”

“What stands out to me when you hear statistics like what Vanessa is saying is that when cases end up in front of a judge, they have the extra burden of trying to figure out what is really going on here and how to protect the defendant’s rights. It becomes almost impossible to do when you look at the backdrop of what took place to get to court in the first place,” said Martin. “As long as there is social justice disparity, we’re going to have disparity in the criminal justice system in terms of having justice for all.”