Monmouth University has been named alongside 104 colleges and universities in the United States, Canada, and the United Kingdom, including Yale University, Princeton University, and Oxford University, in the Paradise Papers, a leak of documents and files that indicate the institutions named had affiliations with offshore accounts, most often, to avoid tax liability.

While the University’s connection to the Papers may not indicate any wrongdoing or illegality on their part, the business practice’s commonality among institutions of higher education raises a question of ethics and moral duty.

The Paradise Papers are the second-largest data leak in history, following the 2016 release of the Panama Papers. Both leaks were obtained by German newspaper Suddeutsche Zeitung, who then shared the material with the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ), a United States based organization that won a Pulitzer Prize for their work on the Panama Papers.

The ICIJ published the Papers in 2016, exposing the methodology behind how wealthy citizens, organizations and institutions avoid paying taxes by keeping funds in offshore accounts.

George Yager, a CPA who specializes in tax compliance and family wealth planning, and provides consultation on tax advisory services to a broad range of clients including management companies and their owners in the alternative investments industry, as well as energy and real estate clients, explained tax avoidance as an action taken to reduce one’s tax liability and maximize after-tax income.

“Tax avoidance is perfectly legal and involves the practice of maximizing deductions, adjustments to income and use of tax credits to lower tax liability within the Tax Code and Regulations. While the legality of tax avoidance is clear, the ethics of it are not. Most taxpayers use some form of tax avoidance to legally lower their taxes such as contributing pre-tax income to a 401(k) retirement plan,” said Yager.

“This would be viewed as both a legal and ethical practice to reduce one’s taxes. But when a tax avoidance strategy entails the use of loopholes in the Tax Code, the question of whether that is ethical may be raised,” Yager continued.

“This would be viewed as both a legal and ethical practice to reduce one’s taxes. But when a tax avoidance strategy entails the use of loopholes in the Tax Code, the question of whether that is ethical may be raised,” Yager continued.

Yager added that taxpayers using this strategy would be legally reducing their tax liability, but it could be argued that by using loopholes they may not be paying their fair share and therefore, not be ethical. “As there is no single definition of ethics or specific rules, the ethical determination must be made by the taxpayer depending on the circumstances,” he continued.

The practice of storing funds in these offshore accounts is not new, and a New York Times article suggests that universities are continuing to use these offshore accounts to avoid taxes and perhaps in some cases even hide investments, while growing increasingly larger endowments. While the purpose of holding money in these accounts varies, the general theme and rationality for holding these funds in these accounts are primarily for tax avoidance.

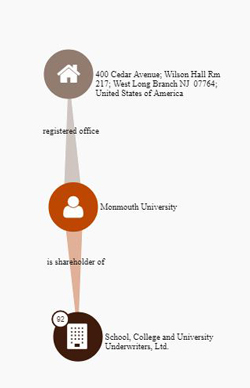

According to William Craig, Vice President for Finance at the University, the school’s involvement in offshore accounts began in the 1980s, and the company used was liquidated in 2001.

“You have to go back to the 80s for this one,” Craig explained. “Back in the 80s, there was basically an insurance crisis where it was becoming very difficult for corporations to get certain kinds of liability coverage at all, and if you did, it was extremely expensive. One of the solutions at the time was for groups of corporations to get together and essentially form their own insurance companies. These were all done because of the way the US laws were at the time. That’s where this comes in in the Paradise Papers – that there were offshore investments.”

According to Craig, two corporate groups were formed, with about 100 of the top corporations in the United States investing in them. The two companies, Ace Ltd. and Exel Capital LTD, were based in Bermuda, according to a 1999 article in The New York Times. According to Craig, these companies influenced the creation of a similar company for schools to get insurance.

“The company formed by the colleges was called something like ‘School, College, and University Underwriters Liability (SCUUL),’” said Craig. “Because of the success of the corporate ones that had been set up, they used a similar model in order to get capital to establish the insurance ‘cooperative’ – that probably isn’t the right legal name, but it’s a group of schools that got together to do it.”

“You had to become a stockholder in the company,” he continued. “That gave you the right to buy insurance, initially, from them. That’s the ‘investment’ that Monmouth had. We were in it until they liquidated the company, around 2001.”

SCUUL was created in 1986 as a response to a liability crisis that was making it difficult to purchase insurance. Reinsurance firms are generally used to avoid risk and financial loss and to provide long term fiscal stability. Bermuda is a popular location for the reinsurance industry because it has no corporate tax and no capital gains tax, according to the New York Times.

Craig said that the University was involved until the company liquidated due to US laws that changed, and a new company replaced the SCUUL, named United Educators, a Vermont based reinsurance company. “We showed up on the list because we were investors in the company,” he added.

Craig is unsure of the total endowment fund invested in the offshore accounts, but explained that at the time administrators and trustees would have had to sign off on this decision. “This was done less as an investment and more a way to get insurance, the risk of not having insurance was great. Excess liability coverage – highest level of insurance coverage – was to protect from that risk of a catastrophic event,” said Craig.

Two major investment pools of money are talked about for the University, according to Craig. “The one talked about most often is the endowment invested for the long-term – the idea of the endowment is to generate income that can then be used for specific university purposes a lot of that money comes from people who make donations – endow a professorship, scholarship fund money gets invested, hopefully forever generates money to be used for those purposes every year,” he said.

The intention behind those monies, is to keep it invested to earn more money, so can be invested in a broader range of types of investments. “Some of it can be in fixed income investments – government bonds, corporate bonds, things that are just going to give you a return of interest – can also be invested in equities – stocks, bonds, things of that nature, they can be invested in real estate and private capital – firms that invest in new businesses, providing financial support to businesses that need additional monies, things like that – can be a very broad range of investments,” said Craig.

The second pool is used for the operating funds of the University and of reserves that the school is setting aside for capital projects, such as new construction, and renovations. “These funds only invest in fixed-incomes since they have less risk of loss, and includes the monies used to operate the school. Tuition comes in and is invested in those accounts, and the pool also pays salaries and utilities. If the board decides to set money aside for a construction project and a contract is signed for the contractor to come and start building, they don’t want to have to worry about their investments turning south and not allowing them to continue the project.” Craig continued.

“As far as how do we invest, in both cases, outside managers are used to invest. In the case of the endowment, there is a firm called ‘Commonfund’ which was formed back in the 80’s from a grant to try and help colleges establish a better way of investing their endowment money; they actually are the school’s chief investment officer – they handle all the details of investing,” said Craig.

The Board of Trustees has an investment committee, who have overall responsibility for oversight of investments of both endowment and operating capital, the pool two funds, and set overall investment policy, and what the University can invest in. During the course of the year, they review those firms, and provide oversight of what they’re doing. The board also maintains oversight regarding the day to day decisions on what is being invested in those outside firms.

Paul Savoth, JD, an associate professor of accounting, believes that Craig’s explanation of how the University ended up in in the Papers indicates the school had a legitimate reason for investing in an off-shore company, different from the reasoning mentioned in the Paradise Papers story.

“I think the Paradise Papers story focuses on tax avoidance strategies and the ability to avoid public scrutiny of the type of investment being made,” Savoth said. “Mr. Craig indicates that the investment was motivated by the need to obtain cost-effective insurance. I don’t understand the legal structure well enough to criticize what the University has done, either legally or ethically.”

Savoth believes that the University practiced a legitimate strategy for several reasons, and does not believe that the usage of these accounts was for any personal financial gain. “The initial investment was made decades ago by a consortium of universities for a legitimate business reason. From what we know, the arrangement has never been challenged by the IRS or another government agency,” he continued.

“The investment has been overseen for decades by our board of trustees, the membership of the board has changed during that time, and yet the arrangement has been consistently approved. This does not appear to be the type of decision that the board members would have personally benefitted from.”

Savoth explained that Monmouth is different when it comes to tax rules because it is a nonprofit corporation that wouldn’t normally pay tax on general income, and that the school may be taxable on certain types of investment income.

“The general benefit to people of moving money into tax havens is that you can move that money out of the jurisdiction of the US tax system and move it into a lower tax jurisdiction in legal ways. As a lawyer and accountant, in terms of the ethics, that’s a little bit of a complicated question – they’re moving money offshore, even though that may sound clandestine, if it’s legal, then it seems to me that they have an obligation to try to maximize the return on those monies and to me the administration has a responsibility to do what they can to generate the greatest after-tax way of return.”

On whether there are negative repercussions or penalties for universities that practice tax avoidance, Savoth believes that legality is key, and the only negative is a tarnished reputation.

“Assuming it’s legal, the publicity is an issue because people will associate that with some kind of unethical behavior, and that’s negative publicity. For-profit corporations are finding that out and moving their HQ’s out of US for tax purposes, and suffer negative publicity because of that.”

While the strategy used was apparently legal at the time, there were some differences of opinion concerning its ethical boundaries.

“To me, doing something like this is not unethical,” said John Buzza, a specialist professor in management and decision sciences department who teaches a course on ethics, diversity, and social responsibility. “In business today, you’ve got to take advantage of any loophole that’s out there, as long as it’s legal – that’s the key. There’s a very thin line between legality and illegality, but offshore investing is done by hundreds upon hundreds of corporations in the USA for various reasons. In this particular case, it’s insurance. If i can get cheaper insurance overseas than I can get here, why wouldn’t I do that?”

Buzza also outlined some of the benefits of offshore investing, some of which included not having to worry about compliance and regulation standards from the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), confidentiality, diversification of money, and the potential tax benefits.

“It’s legal, so take advantage of it,” Buzza said.

“This practice is legal,” said Stuart Rosenberg, Ph.D., an associate professor in the department of management and decision sciences. Rosenberg also teaches a course on business ethics.

“It is acceptable and appropriate. Endowments are tax-exempt, but because they work with private equity funds that borrow money to invest, the money that they earn is taxable. By moving the money to offshore accounts, they are benefiting from existing laws in order to avoid paying taxes,” he said.

“If we separate what’s truly ethical and what’s legal, some people might view this all very differently,” Rosenberg continued. “They might argue that it is not morally right to receive a benefit from something if it’s not being paid for. In the case of higher education, perhaps the question of fairness could be addressed by demonstrating how endowments are being used to provide a public good. Need-based scholarships are one example.”

Kenneth Mitchell Ph.D., Chair of the Department of Political Science and Sociology and an associate professor of political science, believes that in a globalized society that is becoming increasingly difficult to tax, a tarnished reputation shouldn’t exist from these business practices.

“What you see is the ability to tax capital that is so mobile has become incredibly difficult. It’s not surprising that this is going on. When this information came out [The Paradise Papers]. This boundaryless world is increasingly visible and on display for us. Gone are the days of just taxing everybody’s wealth. I don’t think anyone cares. I don’t think anyone won’t buy their product or not go to Harvard or Monmouth because they turned up on these papers. I don’t think it’ll impact anyone’s decisions,” Mitchell said.

“The idea of how you want to tax yourself and spend your money – these are choices. I think that most people have seen for quite a long time that it’s going to be impossible to tax wealth. Monmouth isn’t any different than anyone else on the long list of for-profit and non-profit institutions that turn up on these things. I don’t think they did anything wrong – this is so widely practiced,“ he concluded.

“In theory, the law is supposed to follow what society believes is ethical,” Rosenberg continued. “As long as tax shelters are within the law, however, organizations will surely exploit that.”

PHOTO TAKEN by Coral Cooper