Pink Floyd, Queen, The Doors, The Talking Heads, Phish, and The Pixies, what do all these iconic bands have in common? From the freezing Northeast to sunny Southern California to whatever the hell happens in England, these bands were all born on a college campus and started in a ‘Do-It-Yourself’ (DIY) music scene.

For those of you who are like me and would much rather go to a dingy basement and thrash around to some rockin’ live music and perform a set than feel like sardines covered in sweat, jumping to the US Top 40s in an even dingier fraternity basement, DIY shows are for you. You may ask yourself, where do I go, where do I look, or why haven’t I heard of anything around here? I’ll let you in on a little secret…We’re everywhere if you know the right people. And if you’re reading this, welcome to the club.

This is a DIY How-To Guide, comprised of advice from conversations I’ve had with my band as well as some other local New Jersey-based DIY bands and venues to help guide you through the trials and tribulations of getting your band from practice space to show.

Step 1: Work the Room

The biggest thing when it comes to any part of the music industry, but especially the DIY music scene, is networking. A key takeaway I’ve learned since becoming a proactive member in the Jersey scene, attending shows in Long Branch, Ewing/Trenton, and New Brunswick, is that meeting people and building those connections is everything. Getting involved in your local scene and the scenes close to you is such an easy way to meet some awesome like-minded people, other local bands, venue owners, and music lovers in general.

Ray Zando, a Monmouth University Music Industry alumnus, recommends that local musicians should “be at shows and present in the local scene.” As the vocalist for the local bands Malibu and Holly Hox, Zando said, “You meet people [at shows] you want to play with or even just network with, and it’s not even formal.” He suggested it’s as easy as saying, “Hey, this is a cool spot, I have a project and would love to play here.”

Similarly, Rory Alene, a fellow musician and co-founder of the queer/trans-run DIY venue Milky Mansion in New Brunswick, emphasized building community. He said, “Go to shows! It can be scary to go out and meet people, but I think the best part of a music community and the best way to get out there (and the foundation of any community) is showing up for each other and prioritizing formulating genuine connections.” Alene also suggests that if there is a band you’d like to be on a potential bill with, it’s not a bad idea to go to their shows and “get a sense of their sound, how they run things, etc.”

Step 2: Slide Into Their DM’s

This next step can be daunting. Believe me, I know. The Jersey DIY music scene uses social media platforms, primarily Instagram and its direct message (DM) feature, as their main source of communication. It’s one thing to meet and talk to someone face to face with a few drinks in you at a show and another to virtually introduce yourself and then anxiously wait for a response from what feels like an abyss on the other side disguised as a profile.

Zando suggests being personable, yet transactional, when reaching out to local DIY venues. The formula we came up with is to 1) Send your initial message from your artist page instead of your personal account. 2) If you’ve been to the venue before, mention it and tell them you would love to see if you can work out a day to play there. 3) Send any songs you have released, and if you don’t have songs out yet, send a demo or list any comparable bands.

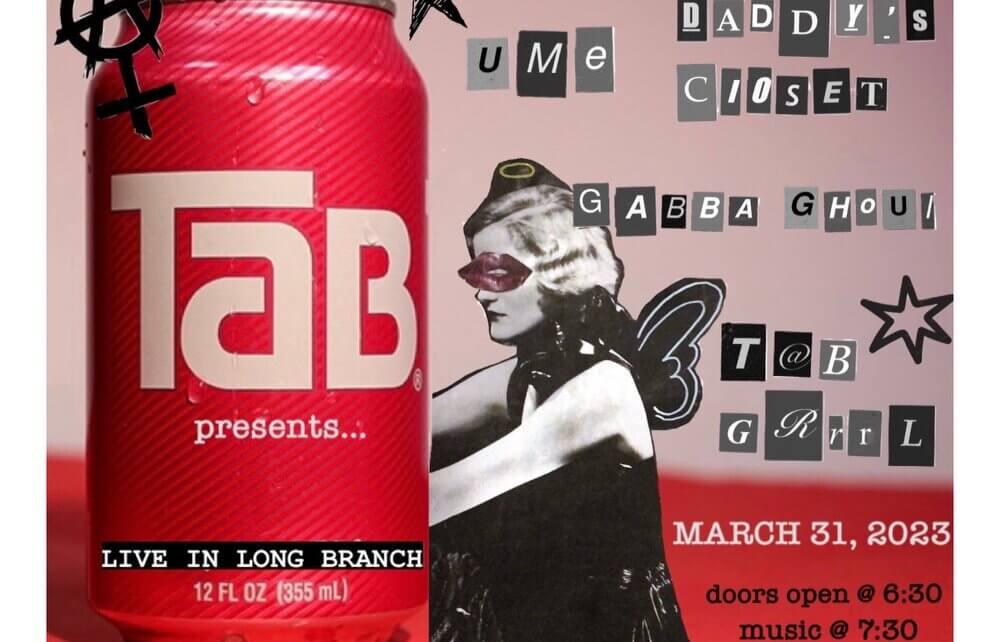

Moon Motel Productions, a New Jersey LLC co-founded by Nick Hubner, PJ Ponce, and Kaden Mobley is one of the only consistent basement show hosts in Long Branch. They explained that they “have had many great performers come with no music on streaming platforms that have been outstanding and surprised us!” They also introduced me to the term “Electronic Press Kit (EPK).” Moon Motel recommends that any artist or band “should create an EPK for themselves to send out to promoters and other industry professionals.” They explained, “There are tons of resources online on how to create one and plenty of templates on digital design suites, like Canva. In a nutshell, the essential components of an EPK include an artist bio, social media links, contact information, high-quality photos and/or videos, and a music sample. If an artist has a specific date they would like to perform, they should mention it when messaging promoters and sending them their EPK.”

If a DIY venue or a dive-bar venue, like The Chubby Pickle in the Highlands, for instance, also has an email listed, shoot them one. Also, if the venue doesn’t get back to you, don’t be discouraged! There’s no harm in sending a follow-up message or email. “Always send a follow-up! It looks good and proves that you actually do wanna play there,” said Zando.

Step 3: The Mic is Open

If you’re not sure your band is ready to perform a full set just yet, there are alternatives to get your foot in the door. “It’s always a good idea to play open mics or shows with an open sign-up,” Alene recommends to bands just starting out. Zando also discussed open mics but indicated that this step might be easier for those with an acoustic or solo set, as some places that hold open mics may not have a drum kit or be accommodating for full bands. Keep this in mind when preparing for an open mic, but don’t let it deter you from searching! Places to look for solo or full band opportunities for open mics and sign-ups in the Jersey area include local DIY venues, coffee shops, restaurants, or even on-campus events.

Mikey Sanchez, a Monmouth University Music Industry major and active member of Blue Hawk Records, walked me through his experience at a Blue Hawk campus-sponsored open mic night last semester. “You just go, and then you sign up to see when you play when you get there. It’s like acoustic vibes because it’s in the Great Hall, so it’s really echoey. The open mics are fun and good to chill, hang out a bit, and play a song or two. No pressure whatsoever.” Opportunities like this are also a great way to practice performing, and Blue Hawk isn’t the only club that hosts them! A few other clubs that host open mics include MU Players and the Black Student Union.

Step 4: And… We’re Live!

College students have an interesting advantage right now. We have the opportunity to utilize a lot of different outlets that we would otherwise not necessarily be exposed to. For instance, the lead guitarist for my band T@b Grrrl, Julia Landi, is the music director of The College of New Jersey’s radio station, WTSR. Because of this, we were given the chance to debut our band at their live on-campus event, WTSR Underground.

Landi said, “College radio and the local music scene have always worked together in a way. They’re both supported by people genuinely passionate about what they are doing and who foster a sense of community to a lot of different people. Lots of college radio stations do live music events featuring local artists, and since they’re run by students, many will also feature local artists on air.” College radio-sponsored events are great for exposure and meeting more local bands you may not have met yet! If you’re looking to perform at a college-radio event soon, Monmouth University’s student-run radio station, WMCX, is hosting a “24-hour fest” on April 14 and would love to have you! Email wmcxpr@monmouth.edu to see what slots are still available.

Moreover, off-campus college students have a shockingly underutilized resource: their house. The local band Malibu, formed by Monmouth University students in 2017, employed this effectively pre-pandemic, and Zando’s new band Holly Hox does the same now. These local bands cracked a Jersey DIY music scene code, and the secret is this – anywhere is a stage if you make it one! From living rooms to basements to backyards, you can have a show anywhere while subsequently building and strengthening your local scene.

However, there are some things to consider while planning and running a house show yourself. Things to keep in mind sourced from the zine, “How to Run a Show House: A DIY Music Guide,” co-authored by Rory Alene: (1)There are many spaces of a house that can be used to throw a house show, so it’s important to start by picking one. (2) Safety is important, so having a “known point of contact” is key and helps people know who to talk to if they need anything. (3) A suggested donation of $5 is standard, but no one should be turned away for lack of funds. Musicians should be paid, but money should also be allocated to the house fund. Therefore, 20% of the proceeds to the hosts is suggested. (4) Sound is imperative, so ensure you have a good system. Things you’ll need: PA speakers, a mixer, mics, cables, mic stands, wedges, DI boxes, and amps. (5) Choose your bands (a bill should consist of about 3-4 acts), make a flyer, and start promoting! (6) General hosting tips: have someone working the door/security, keep snacks and water accessible for anyone who might need them, make your zero-tolerance policies known (racism, homophobia, sexual assault, etc.) and abide by them, know your city/town’s noise ordinances, and reach out to your neighbors beforehand!

Step 5: It’s Time to Rock!

You’ve done it. You’re ready to go! Your venue and date are secured, now, where do you go from here?

Show etiquette includes making sure you have prepared a proper set within the given time allocated by the venue. Sets will usually be about 30 minutes, but a good rule of thumb is to simply ask the venue if you’re not sure how long they want your set to be. “Don’t go over, and you can go under, but you should shoot for 20-25 minimum if you’re going to go under,” said Sanchez, who’s also the vocalist for the local band Buffout. In addition, he suggests that maintaining contact with the venue and bands on the bill is key and that it is also standard to ask about a backline and who is bringing what. Sanchez, sporting a Title Fight band t-shirt and his long ebony hair down to his chest, explained, “a backline are things that the venue already has there and things that aren’t being switched out. For example, an amp or drum kit can be backlined minus breakables. You could be like, ‘oh, we have this really good bass amp everyone can just use, so it makes it easier on everyone switching out instruments.’” A band should typically bring their instruments, foot pedals, and breakables for the kit, which include snare, cymbals, and sometimes stands.

Other common show decorum includes getting to soundcheck on time– the tardiness of one band can cause the entire show to be set back. It is also just common courtesy to be respectful and nice to everyone involved and not leave right after your set unless previously discussed. It’s always suggested to “stay for at least a couple of bands,” said Sanchez.

The last piece of advice I’ll leave you with is this: “Wait until you’re tight to play, and don’t rush your releases. Get the songs together and make sure you’re really solid even if it takes a couple of months,” suggests Zando.

The scene will always be here for you, and one thing I’ve had to learn is that everyone does things at their own pace, so take your time. Know that it’s also okay to be nervous. When you feel well-rehearsed and ready, we’ll be here, ready to rock out and cheer you on!