Colin Kaepernick made national headlines when he knelt for the National Anthem during a September 2016 game between the San Francisco 49ers and the Green Bay Packers.

Stating that his stance was a protest against racial injustice in the country, he continued to kneel and was joined in his protest by other athletes such as U.S. women’s soccer star Megan Rapinoe and Denver Broncos linebacker Brandon Marshall, according to SBNation.

As time went on, the protests received less and less attention, until President Donald Trump brought the topic back into the limelight, saying “Wouldn’t you love to see one of these NFL owners, when somebody disrespects our flag, to say, ‘Get that son of a ***** off the field right now, out, he’s fired… For a week, (that owner would) be the most popular person in this country. Because that’s a total disrespect of our heritage. That’s a total disrespect for everything we stand for,” at a campaign rally for Alabama Republican Senate candidate Luther Strange.

Following Trump’s comments, dozens of players from various professional teams knelt at games the next day, including the Baltimore Ravens, the Jacksonville Jaguars, and the New England Patriots, among others. Team owners, including Trump donor and Jaguars owner Shad Khan, also joined the protests, as others denounced the president and his commentary on social media, according to Salon.

“The take a knee protest movement now means different things to different people,” said Joseph Patten, Ph.D., an associate professor in the University’s political science and sociology department.

“The take a knee protest movement now means different things to different people,” said Joseph Patten, Ph.D., an associate professor in the University’s political science and sociology department.

“What we’re seeing here in the kneeling was that the protests wanted to call attention to the issues that were facing their lives – maybe not directly, but the general human race,” said Jennifer McGovern, an assistant professor in the University’s political science and sociology department. She also focuses on how sports can both reflect and challenge social inequalities, such as race, ethnicity, social class, nationality, gender, and sexuality. “Once Trump weighed in, the conversation started to be about something else,” she continued.

The controversy also trickled down into college and high school teams. Gyree Durante, a backup quarterback at Albright College, was removed from the team after he knelt twice during the National Anthem, according to CBS Sports.

Two high school football players at Victory and Praise Christian Academy in Crosby, TX were also removed from their team after they knelt. However, at Glen Burnie High School in Maryland, three students knelt at a homecoming game on Friday, Oct. 13 and were supported by their school, according to the Capital Gazette.

“When this topic first arose last year, I had discussions with our coaches, who in turn had discussions with their student athletes,” said Marilyn McNeil, the University Director of Athletics.

According to McNeil, the University currently has no rules, nor do they apply any pressure to its athletes, that could limit or prohibit them from exercising their freedom of speech. However, the University athletes are not usually on the field when the anthem is playing.

“In 99 percent of college football games, the anthem is sung before the teams come out of the locker room,” said Greg Viscomi, the Associate Athletics Director for New Media and Communications at the University. “In 11 years at Monmouth, I think only one time we’ve been out of the locker room.”

According to Viscomi, when the University played the Bucknell University Bisons on Saturday, Sept. 30, it was the first time “in many years” that the team had been on the field for the anthem. He added that all members of the football team stood.

“I just don’t think that in the middle of the season they want to take attention or focus away from the team and what they are trying to accomplish,” Viscomi said.

According to the University’s Student Athlete Handbook, “All interviews must be set up by a member of the Athletics Communications Office, preferably through the specific sport’s media contact. This includes requests from newspapers and all other media outlets, including on-campus entities and student requests.”

The handbook also states that students cannot participate in an interview without prior knowledge of the Athletics Communications Office, and interviews should not be conducted over e-mail, as “face-to-face interaction and/or a phone conversations are much easier to manage.” The handbook also states “Phone interviews will be done in the Athletics Communications Office, unless you are instructed otherwise.”

The handbook also states that students cannot participate in an interview without prior knowledge of the Athletics Communications Office, and interviews should not be conducted over e-mail, as “face-to-face interaction and/or a phone conversations are much easier to manage.” The handbook also states “Phone interviews will be done in the Athletics Communications Office, unless you are instructed otherwise.”

“This type of arrangement is normal for public relations,” said Kristine Simoes, a specialist public relations professor at the University. “You are a representative of the organization. If they’re quoting you as an employee, representative, or in this case, Monmouth athlete, then your name is tied to the company. Therefore, the company runs a risk when they let you speak freely without them; it could come back on the company.”

Viscomi assured that the University as well as many others have this policy in place to protect student athletes, rather than censor them.

“We do not censor our kids,” said Viscomi. “These guys are really great kids, and they are really responsible. We’re just here to make sure that they are being responsible, and have put thought into what they say.”

“If that’s (the policy) consistent across all sports and at all times, I can understand why they would have that policy,” said McGovern. “What often happens is that a student will take something out of context, or something comes off as the University’s position when it’s not. Provided that [the policy] is always consistent, and that has been the policy prior to these issues coming up, the fact that the individual is balanced with someone representing the institution makes sense.”

“There are two viewpoints on it,” said Simoes. “There’s the viewpoint from the organization, which is to protect the organization’s reputation and brand at all costs. As a public relations person, that’s what you do. On a personal side, there’s a first amendment right to the freedom of speech – but that’s only a personal freedom. It doesn’t apply to you representing anyone other than yourself. You can’t wear a Monmouth sweatshirt and be a Monmouth athlete and go on camera and say whatever you want, because at that time, you are representing Monmouth.”

“I think so long as the University isn’t censoring the players, if they’re just saying we need both voices to be at the table, that’s a good thing,” McGovern continued. “More voices at the table is always better. The policy encourages exactly that.”

“I think so long as the University isn’t censoring the players, if they’re just saying we need both voices to be at the table, that’s a good thing,” McGovern continued. “More voices at the table is always better. The policy encourages exactly that.”

“We haven’t addressed it since people started taking the knee or things like that, but we talk about social issues all the time,” said King Rice, the Head Coach of the University’s Men’s Basketball Team, in an interview with the Asbury Park Press in fall of 2016.

Rice has since declined to comment on this story, along with the entirety of the men’s basketball team.

However, Women’s Basketball Head Coach Jenny Palmateer commented on the issue, “I really don’t think that politics has a place in college sports. I think it should stay in its own lane, and let athletes be athletes. The team atmosphere becomes too divisive.”

Alexa Middleton, a sophomore forward on the women’s basketball team, believes that the issue is important. “It’s about equality,” said Middleton. “Whoever wants to stand up for equality, I wouldn’t stand in their way. I’d fully support it if it’s coming from a good place. It’s about making the world a better place.”

Other athletes from the University teams also had their own opinions on politics being present in athletics.

“I would say that [politics] do have a place in sports,” said senior football defensive back Kamau Dumas. “But we’re a team, and our main goal is to win games. Sports are a place where people come to forget about the real world and get away from outside distractions. However, this issue is something that we as a society can’t run away from. I support all of my teammates. We’re brothers, and any team should stand behind one another.”

“I don’t think [politics] have as big of a place in college football as it does in the NFL,” said junior wide receiver Reggie White, Jr. “We play as a team. I would definitely support a teammate taking a knee. It’s important to know where they are coming from, and what’s going on in the world today.”

Sophomore tight end Nick Venier, who is also a United States Airforce veteran and President of the Student Veteran’s Association, added to the conversation discussing whether kneeling during the National Anthem implies disrespect toward the Nation.

“Personally, I would never take a knee, but I support my teammates in how they want to express themselves,” Venier continued. “People have the right and freedom to do so if they want. As a veteran, we understand the customs and courtesies associated with the flag, so many probably wouldn’t take a knee. But a lot of veterans, including myself, wouldn’t be offended as a veteran if someone was to do it, because they have the right to do so,” he said.

“Every citizen has the right to express themselves,” said Football Head Coach Kevin Callahan. “Freedom of speech and expression is important, especially in an academic setting.”

“People say that there is no place for politics in sports, that politics have no place in athletics, but sports are inherently political,” added McGovern, pointing out that taxpayer dollars may fund part or all of the stadiums as an example. “You can’t say you want political gestures out of sports, and have that.”

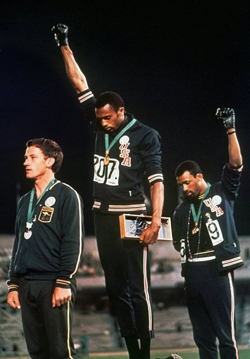

McGovern also pointed out that political protests in sports is not entirely uncommon, highlighting the 1968 Summer Olympics, where gold-and-silver placing medalists Tommie Smith and John Carlos raised fists in what was widely viewed as a black power salute as they stood on the podium for the national anthem. The United States Olympic Committee suspended both athletes and sent them home.

During the 1972 Summer Olympics, track athletes Vince Matthews and Wayne Collett, were barred from the competition after they took the podium in Munich and did not face the flag as the anthem was played. According to the Times, the pair “…stood casually, hands on hips, jackets unzipped… they chatted and fidgeted.” After the anthem ended and they left the stand; they were booed, and Collett “gave a black power salute” while “Matthews twirled his medal.” The two were later barred from competition by the International Olympic Committee (IOC).

In March 1996, the National Basketball Association (NBA) suspended Mahmoud Abdul-Rauf, a player for the Denver Nuggets, for refusing to stand during the anthem, according to The New York Times. According to Abdul-Rauf, who had converted to Islam in 1991, he did not believe in standing for any nationalistic ideology.

“People are really asking the question, ‘Should political gestures that make me uncomfortable be in sports?’” McGovern said. “And I would say, ‘Why not?’ I think it takes a lot of courage for an athlete to make a political protest; they have a lot to lose.”

Monmouth Athletics has continued the dialogue with both coaches and athletes alike. “We continued to have the conversation and will continue to discuss the topic as long as it remains relevant to the current athletics landscape,” said McNeil.

IMAGE TAKEN FROM Political Storm

IMAGE TAKEN FROM CBS Sports

IMAGE TAKEN FROM @camdasilva on Twitter

IMAGE TAKEN FROM The New York Times