Though students are back in the classroom and the pandemic seems to be a thing of the past, many on this campus and in society at large are still feeling its effects physically, emotionally, and financially. Individuals, families, and organizations had to adjust their lives and finances in order to weather the most challenging global event of this century, so far.

During the pandemic, Monmouth University, likewise, implemented a number of changes in order to curb financial and academic strain on faculty and students. In April 2020, Patrick Leahy, President of Monmouth University, issued a notice to faculty members titled “Fiscal Realities.” Within this memo, five points were stated to be the main focus of the University: “Freeze Hiring,” “Control Non-Essential Operating Expenses,” “Suspend Capital Projects,” “Implement Senior Administrative Salary Reductions,” and “Develop Furlough Program.”

An update on this email was later sent in October 2020, with another five points of focus. These were “Freeze All Hiring,” “Control Non-Essential Operating Expenses,” “Eliminate Capital Funding Allocation in the Operating Budget,” “Reducing the Budget Contingency,” and “Offer Voluntary Separation Program.”

“I’m really proud of the way the University weathered the pandemic in so many ways,” Leahy began. “[Focusing financially], we were able to break even every year during the pandemic, so we never had to do any deficit spending, in part because the government helped offer grants. They really came to our rescue to make sure that we could continue to serve the students well despite the disruptions.”

According to U.S. Department of Education, “The Coronavirus Act, Relief, and Economic Security Act or, CARES Acts, was passed by Congress on March 27th, 2020. This bill allotted $2.2 trillion to provide fast and direct economic aid to the American people negatively impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic. Of that money, approximately $14 billion was given to the Office of Postsecondary Education as the Higher Education Emergency Relief Fund, or HERF.”

Despite the government’s financial help during the pandemic, the University leadership decided to implement six-month pay cuts for senior administration that include University President and Vice Presidents. President Leahy took a 25 percent cut whereas cabinet members took a 10 percent cut, according to the “Fiscal Realities” email. These cuts would be effective starting May 1, 2020, and continue for six months.

“I took a cut and the senior administrative team took a cut to get us through those six months, and then those were restored,” Leahy explained.

Christopher Maher, the Chairman of the Board of Trustees—and also the Chairman and Chief Executive Officer of OceanFirst Bank Director of the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia, Director of Hackensack Meridian Healthcare Services, Inc., Director of Hackensack Meridian Nursing and Rehab Ocean Grove, and a Trustee of Hackensack Meridian Health Foundation, Inc., among other notable roles—emphasized Leahy’s 25 percent salary cut for six months during the pandemic. He said, “[Leahy] then subsequently requested a significantly lower base salary to provide a bit more financial flexibility for the University. Any additional compensation in the form of bonuses or added benefits is provided at the sole discretion of the Board, based on the President’s performance against annual goals. In the Board’s opinion, we are fortunate to have one of the finest university presidents in the country. We are comfortable and confident that compensating him appropriately is in the best interest of our students and the future of the University. This is particularly important at a time of significant change in higher education.”

While the six-month cuts were instituted in 2020, 990 filings of the University show staggering administrative compensation numbers during the pandemic years 2020-2021. We received a tip from a concerned employee about the 990 filings and found them to be publicly available documents through ProPublica’s Nonprofit Explorer. We reached out to the NJ Center for Nonprofits to seek guidance and clarification on the various compensation columns that appear in the filings, particularly the Column F. In an email statement we received, they explained, “[In] Part VII of the Form 990… Column F is usually used to report things like deferred compensation (e.g., pensions, retirement plans of various types), employer-paid health benefits, healthcare benefits paid with pre-tax dollars, and the like. In some cases, executive compensation is also broken out further in Schedule J. (Monmouth’s filing does include this schedule.).” Schedule J of the University’s 2021 filing reports that compensation is based on “housing allowance or residence for personal use,” “health or social club dues or initiation fees,” and “personal services (e.g., maid, chauffeur, chef).” Schedule J of the 2022 filing does not include personal services but does include “first-class or charter travel.”

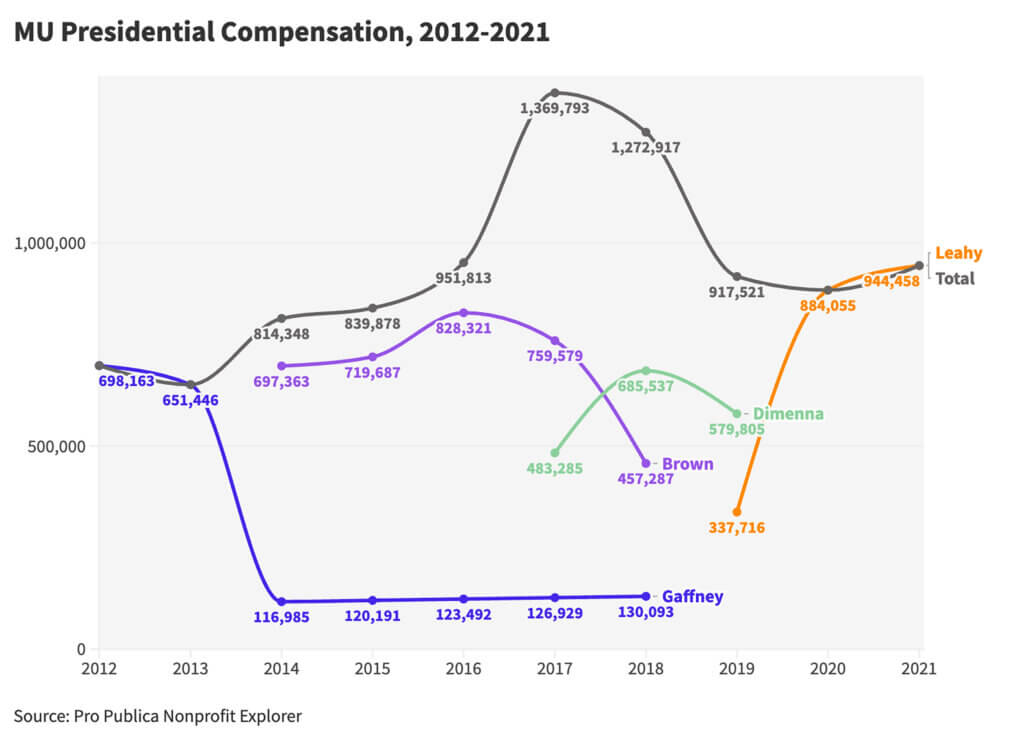

What the 990s show us is the compensation for the top 20 highest paid individuals at the University. For the University’s fiscal year ending in June 2021, presidential base pay was $702,378 with a deferred compensation of $181,677. Other notable pay and deferred compensation include King D. Rice, the head basketball coach, with a base pay of $548,501 and deferred compensation of $63,859; William Craig, the Vice President for Finance, with a base pay of $313,561 and deferred compensation of $55,520; Patricia Swannack, the Vice President for Administrative Services, with a base pay of $288,503 and deferred compensation of $49,929; Donald Moliver, the Dean School of Business, with a base pay of $287,234 and deferred compensation of $51,455.

For the University’s fiscal year ending in June 2022, these numbers fluctuated slightly. Presidential base pay rose to $834,926 with a lower deferred compensation at $109,532, Rice had a lower base pay of $525,715 and deferred compensation of $62,628, Craig had a lower base pay of $312,332 and deferred compensation of $54,357, Swannack had a higher base pay of $323,906 and a lower deferred compensation of $38,520, and Moliver had a higher base pay of $295,438 and deferred compensation of $50,623. Other administrators are listed on the 990 forms, as well. For example, on the June 2022 filing, current Interim Provost Richard Veit, then Interim Dean of the School of Humanities and Social Sciences, base pay was $177,138 and had a deferred compensation of $100,780. In addition, a number of former provosts and deans were also listed in the top 20 highest paid individuals.

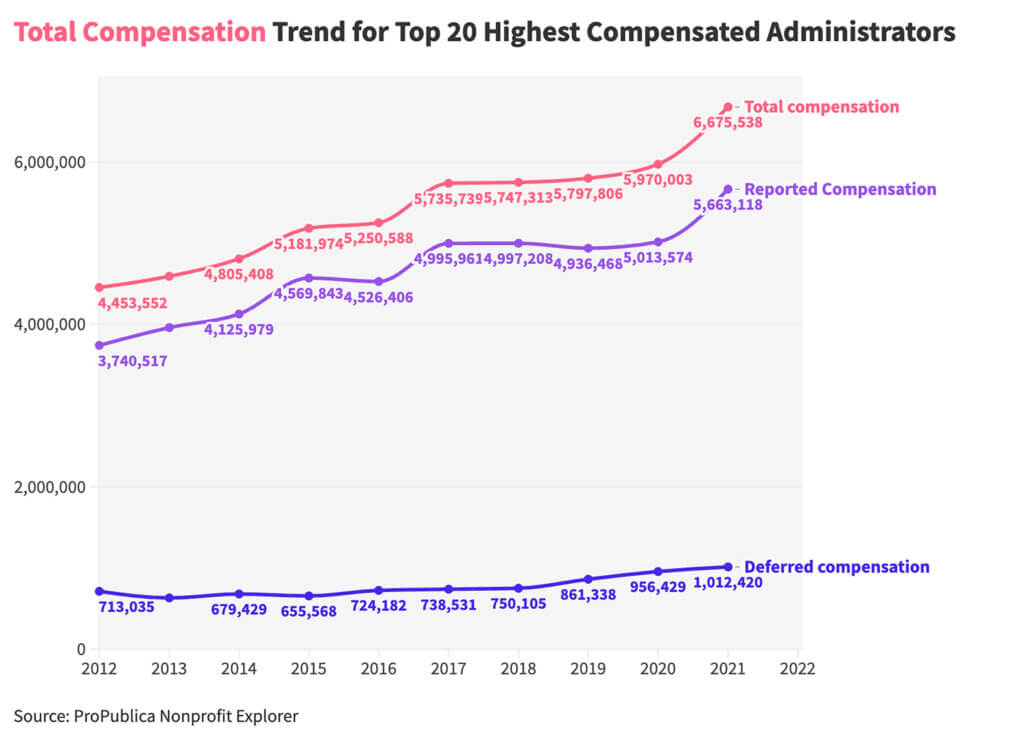

While there are differences in compensation over these two years, the data show consistent growth in executive and administrative pay at Monmouth. For example, President Leahy’s total compensation in just one year from 2020-2021 rose 6.7%, which is almost three times higher than an average increase for administrators, according to an Inside Higher Ed article published on April, 25, 2021. The article cites a report from the College and University Professional Association for Human Resources that found that, “The median salary increase for administrators between 2019-20 and 2020-21 was 0.36 percent… The minor pay bump is the lowest increase for administrators since 2010 — during the Great Recession. This year’s dip [2021] also pulls down the three-year average increase for administrators to 1.92 percent.” Trends in executive and administrative pay at Monmouth can be traced before the pandemic. In fact, a ten-year trend shows consistent increases in base compensation and deferred compensation. While the 2020-2021 6.7% increase in President Leahy’s compensation is not the highest in the last ten years, the highest was President Brown’s compensation in 2015-2016 that went from $719, 687 to $828. 321 — which was 15% increase in just one year—it is still significant since it happened during the pandemic and is higher than average increases.

Graph. 1. Compensation Trend for 20 Highest Compensated Administrators, 2012-2022

When asked to further explain his compensation, President Leahy said, “I do not comment on my own compensation.” He explained, however, that the Board of Trustees sets compensation with the help of a compensation consultant. Maher described the process when determining the amount of presidential compensation.

“The Board of Trustees sets compensation by using a six-person compensation committee and incorporating feedback from all 40 trustees,” Maher said. “The President’s compensation is driven by performance against board-designated objectives, which vary depending upon the issues and opportunities facing the university in a particular year.” He continued by saying, “While specific objectives vary, they always include performance for academic excellence, a safe and enriching student experience, and financial performance.”

Maher also explained, “The process always includes a review of compensation levels at other, similarly-situated institutions to ensure that the President’s compensation is commensurate with market levels. An outside expert in higher education compensation also advises the board through this process and provides external data regarding compensation trends.” Our examination of 990 filings for two comparable and similarly-situated institutions, Elon University in North Carolina and Rider University in New Jersey, show significantly lower compensation for their presidents. In 2021 filings, Rider’s President Gregory G. Dell’Omo received a total of $661,936, and Elon’s President Constance L. Brook received a total of $613,143. Comparatively, President Leahy received total compensation of $884,055 in 2020, and $944, 458 in 2021. Both universities have a larger number of total student population (Rider with 8,408 in 2021 and Elon with 7,123 in 2022-2023, according to their websites) than Monmouth, who had 5,434 students in 2021 and 4,981 in 2023, according to data from the Office of Institutional Research and Effectiveness.

Graph. 2. MU Presidential Compensation, 2012-2021

In comparison, according to AAUP’s 2022–23 Faculty Compensation Survey, average salary for full-time faculty members rose “4.1 percent, the greatest one-year increase since 1990–91.” However, according to the same report, “Real average salaries for full-time faculty members decreased 2.4 percent, the third consecutive year that wage growth has fallen short of inflation. (The CPI-U increased 6.5 percent in 2022, 7 percent in 2021, and 1.4 percent in 2020.)”

A long-time, full professor at Monmouth, who asked for their name not to be printed, cited inflation as a cause for students and faculty to worry about their finances, especially following the pandemic. “Right now, inflation is making it harder for people to make ends meet, and the president made the decision to increase tuition during the pandemic. Students and faculty are worrying about how to afford gas and groceries,” they said. They also expressed concern and surprise with levels of executive compensation at Monmouth. “It is frustrating to know that while the rest of our community’s financial struggles are getting worse, the person at the top’s financial situation is actually improving.”

Johanna Foster, President of the Faculty Association of Monmouth University (FAMCO), Associate Professor of Sociology, and Endowed Chair of Ethics, said, “It is really startling to see a trend line that looks a lot like the skyrocketing executive pay we have witnessed in the corporate sector in the last few decades. Even in the corporate sector, these kinds of excessive compensation packages are shocking and troubling, but to see this trend in the non-profit space of education is just heartbreaking—especially since so many students and employees continue to struggle to live and work and go to school in and around Monmouth County.”

Dickie Cox, Treasurer of FAMCO and Associate Professor of Communication, said, “Faculty morale across campus has felt low for a number of years.” A number of faculty members are also aware of the increases in administrative compensation, according to Cox. “Admin wages rise while the faculty are being asked to do more with less,” he said. “This includes an increased reliance on part-time faculty who are grossly underpaid while we are not hiring tenure-track faculty lines at the rate the tenure track and full-time faculty are leaving the University.”

Nathaniel Cruz, a senior communication major, described what the executive compensation reflects from the perspective of a student. “As a student, it’s hard to understand how this is possible for the President and select cabinet members,” he said. “Especially during COVID, at a time in which classes ran virtually and there was no involvement physically on the Monmouth campus, it’s genuinely upsetting to see just how much our President earned during a time which was detrimental for most Monmouth students and their families… I continuously question how [this level of compensation] remains possible as we are continuously told of the University’s fiscal hardships.”

Comparatively, faculty pay at Monmouth in the last year rose 3% as negotiated by their union contract. In addition, many stipends that faculty receive for other work unrelated to their immediate teaching have said to be eliminated. The aforementioned long-time, full professor who wished to stay anonymous for this article explained, “Faculty are forced to either stop fulfilling those roles or to do this work ‘out of the goodness of their hearts.’ These types of sacrifices are concessions many faculty would be willing to make (and have made in the past) if the University was really in dire financial straits, but knowing that this is a time when administrators are actually making more money calls into question whether these sacrifices are really needed, or if this is just messaging being put out there to force faculty to work more for less money—and at the students’ expense.”

Another growth trend at Monmouth, however, also not exclusive to Monmouth, is tuition growth. In the last ten years, tuition has been steadily increasing.

Graph. 3. Monmouth University Tuition Growth Trends, 2012-2023

For example, as the graph shows, ten years ago in 2013, tuition was $30,390. Currently, it is $44,098. This is a 45.1% increase in ten years. Nationally, college tuition inflation averaged 12% annually from 2010 to 2022, according to an article by Education Data Initiative. During the pandemic at Monmouth, 2020-2021 tuition for students also rose by 2.5% and again for the 2021-2022 academic year by 3.75%. This was the lowest tuition increase at Monmouth, however, it is still higher than national average according to Bankrate.com, which reports that average private university tuition rose by 2.1% during the pandemic.

With tuition increases, many students are experiencing increases in student loans and, ultimately, student debt. A student, who wished to speak under conditions of anonymity, said, “While the University advertises that they are debt-free, it’s sickening to think that my family and I are continuously asked to shoulder a heavier burden to support University operations each year with increasing tuition rates.”

Tuition rates also may be affected by the amount of overall compensation at the University, Maher clarified, “There are a number of factors that go into setting tuition levels, including: compensation levels, additional services to students, campus maintenance, and the like. Each year [in February] we also set the financial aid budget for the coming year, which is one of our single largest expense items. In an effort to keep the net price at Monmouth as affordable as possible, these expenses have gone up more significantly than tuition increases over the past few years.”

Foster questioned the relationship between administrative compensation and student tuition. “The skyrocketing of compensation for senior leaders in non-profit educational institutions in the U.S. is especially disturbing when we consider how many students are crushed by student loan debt to achieve the dream of graduating from college,” she said. “It can be hard not to wonder whether the increase in extraordinarily high salaries of senior academic administrators is being subsidized in part by student debt. At Monmouth, 75% percent of graduates carry some private or public student loan debt, with an average student loan debt of $27,000. That is really hard to swallow no matter how you cut it, but especially when you look at a trend line like that.”

Besides pay cuts for senior administrators, another subset of the “Fiscal Realities” notice, signed by President Leahy, highlighted hiring freezes as its first bulleted point of measures to be taken in order to mitigate the University’s financial impact. This was described as: “All open and new positions – academic and non-academic alike – are frozen through the remainder of the fiscal year. We will complete searches that are currently underway. Any other essential replacement positions that arise over the next three months must be approved by the Cabinet.”

According to President Leahy, “There was never a hiring freeze. There might have been for the three months that we were really dealing with the pandemic. In fact, we put 180 employees on furlough during that time, which means that their job is guaranteed, but that we would put them on furlough. Most of our employees that went on furlough made more money on furlough than we could pay them because the federal government had offered them an attractive furlough plan. Every one of those employees was offered their job back and was brought back that summer. So, there’s never been a hiring freeze. We are careful about replacing positions, for sure. Every position that goes up, we scrutinize to make sure that we need it with enrollment softening, but there was never a freeze.”

However, the reality of going on furlough for some employees doesn’t seem like such a good deal, in retrospect. A long-time employee of the University, who also wished to stay anonymous, said, “[The University] made it sound very, very enticing, and like you were getting something great. You were getting the summer off, and your job is going to be here when you get back, and I thought, ‘Great, sign me up.’ Now, three years later, I’m still dealing with the tax implications of that time because we were given, I don’t quite recall, $1,500, but no taxes were collected. This was not explained to any of us at the time. I don’t feel like I was ahead. I feel like this was some bamboozlement from the University. It’s put me down more where I have to worry about the IRS and this extra $3,000 that I owe and where I’m going to get it. That’s what the University didn’t tell us about the furlough.”

The question of a hiring freeze is a hotly debated topic, as faculty feel that hiring isn’t keeping up with the demand for faculty lines. “Saying there is no hiring freeze is a game of semantics,” the previously quoted, long-time, full professor who wished to stay anonymous said. “We have many faculty [members] who have retired and they are not being replaced, even in departments where there are more students enrolling in the major. There are multiple job searches that were announced, but then before the candidate was hired, the job search was canceled. And full-time tenure track faculty are being replaced with non-tenure track or part-time faculty (e.g., adjuncts), presumably as a way to save the University money. The administration has an agreement in writing that it is for the good of the University that the ratio of tenured faculty to non-tenured faculty should be kept in check. But they haven’t held up that end of the bargain for years.” “By having non-tenured faculty outweigh that of tenured,” the professor further explained, “means that students are subsequently not experiencing any sort of consistency regarding teaching and mentoring.”

“Perhaps there was no official hiring freeze called as such,” Cox began. “However, over the past few years, there were several rounds of buy-outs and early retirements offered by the administration for faculty and staff alike. The stated goal of those buy-outs was cost savings. Many of those positions were not refilled. When I started in 2016, I recall the pride that Provost Moriarty had in a School of Humanities and Social Sciences school meeting for a talking point that there were 312 full-time faculty members as part of the FAMCO union. In this present semester, that number is 256 full-time faculty members represented by FAMCO. That is nearly an 18% loss of full-time faculty in eight years’ time.”

Through the changing and evolving fiscal realities of the University, most concerningly, our students have been recently affected, as well. Several Education Opportunity Fund (EOF) students and Community Assistants (CAs) of the resident halls reported late stipend payments, despite nearing midterms. One EOF student, who asked to remain anonymous due to a concern with potential retribution, said, “I have received adequate funding through EOF throughout the years. Monmouth easily has the best EOF program in the state that provides students with several resources they need to succeed. However, I have not received my stipend for groceries yet and it is nearing midterms. I don’t think this is the fault of the program but the complexities of the school itself.”

When asked about this situation during our conversation, President Leahy said, “I didn’t know about that. I can call right away and find out if there are any delays in those payments. I’m not familiar with those payments.”

President Leahy followed up shortly after our conversation and immediately looked further into the issue. In an email correspondence, he wrote, “Regarding delays in distributing stipends, there are small travel reimbursements available to EOF students in [the] summer, and we don’t know of any delays in processing those. There are possible financial aid and book voucher refunds for qualifying students, but those take a while to work through financial aid. They should be processed soon. I’ve also learned that CAs were paid based on the University’s payroll cycle, starting on September 5, coinciding with the first day of the term. Moving forward, the university will use the training start date to accommodate an earlier pay date for these students.”

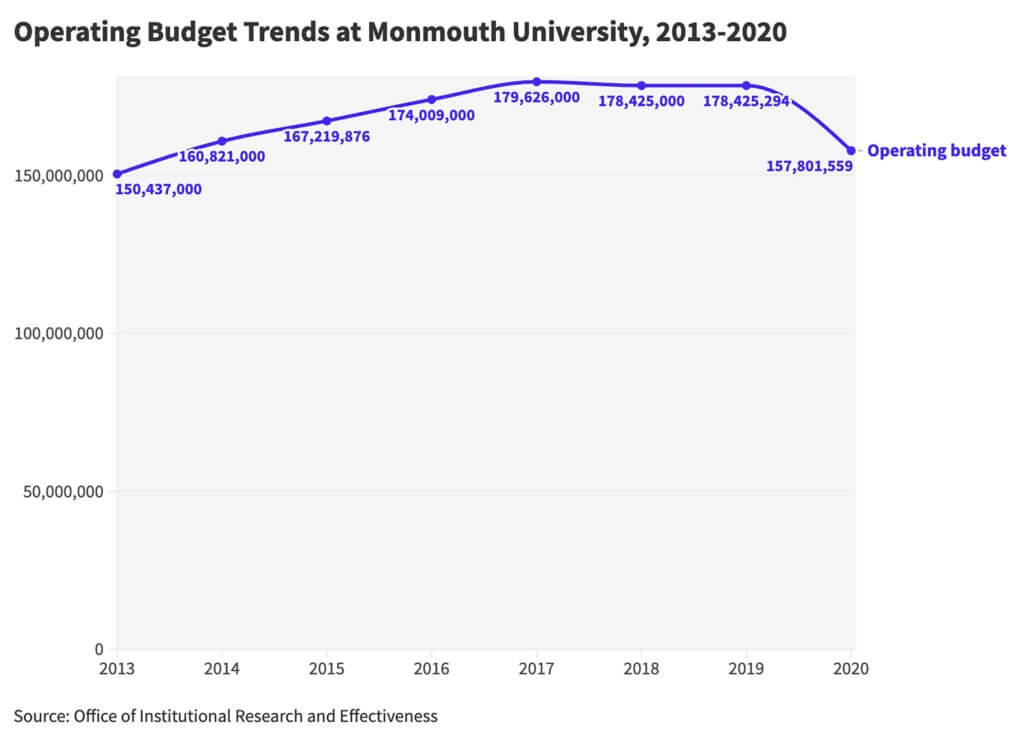

A complex financial picture of the University is further complicated by the dropping enrollment trends, resulting in a lower operating budget. According to the Office of Institutional Research and Effectiveness, the pre-pandemic 2019 operating budget was at $178,425,294, and in just one fiscal year, it dropped by 11.5% to $157,801,559.

Graph 4. Operating Budget Trends at Monmouth University, 2013-2020

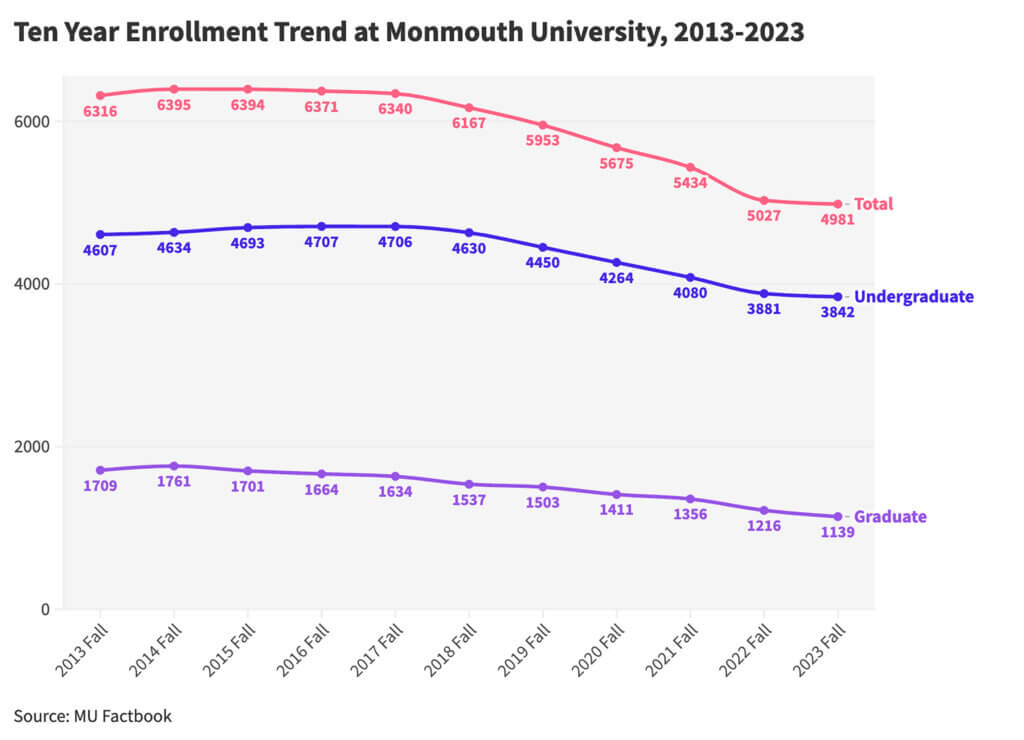

Vice President for Enrollment Management Robert McCaig shared with us enrollment data trends. Student enrollment dropped from 5,675 total students to 5,434 students from Fall 2020 to Fall 2021. Now, in Fall 2023, the total number of students has dropped below five thousand to a total of 4,981 despite an incoming freshman class of 973. In comparison, ten years ago in the fall of 2013, Monmouth enrolled a total of 6,316 students, according to the MU Factbook and the data from the Office of Institutional Research and Effectiveness. As a University that is 91% student tuition dependent, these numbers potentially pose a financial risk.

Graph 5. Enrollment Trends at Monmouth University, 2013-2023

Despite these financial risks, the University announced on Wednesday, Oct. 18 that 75% of $45 million fundraising goal has been raised from various donors for an expansion of the Bruce Springsteen Archives and Center for American Music (BSACAM) that will be built on the corner of Cedar and Norwood avenues. President Leahy said, “What is so exciting about it to me is that it has the potential to positively transform the University, especially if you’re involved in any way in the arts, the humanities, or culture.”

We asked the Director of the BSACAM Eileen Chapman about potentially transformative student learning opportunities associated with the Archives. She said, “We work closely with Professor Melissa Ziobro [Monmouth professor and Curator at BSACAM] and her students. We also work closely with the Music and Theater Department… and we provide internship opportunities for students.”

However, not all members of the University community shared the same excitement. The previously-quoted, long-time, full professor who wished to remain anonymous acknowledged the benefits that the expansion could pose but also said, “At the same time, it raises questions about University priorities. Should we be expanding when our student tuition is going up, we can’t afford to hire full-time tenure track faculty, and we are cutting back on things like academic advising because financial times are tough? The same level of attention that is being paid to expanding needs should be paid to meeting the needs of the faculty and students who are currently here.”

From a student perspective, Cruz wondered about University priorities, as well. “Frankly I find the announcement of this building ridiculous,” he said. “Primarily, this is not what our campus needs right now; increased parking, more accessible commuter spaces, increased study halls, greater library access, and stronger advising teams for students are all examples of things our institution needs desperately. As a student, it is deeply frustrating to see the ways in which our requests and needs are continuously overlooked and ignored.”

An alum Mark Marrone, who graduated in 2020, questioned how BSACAM actually contributes to student learning. “With the addition of the BSA to the University, it’s clear the administration cares more about making a name for Monmouth rather than thinking of the students’ needs first,” he explained. “While it’s an excellent opportunity for the University to gain global recognition, the administration failed to consider this project as a new modernized building for music and arts students who are long overdue for upgraded facilities and equipment. The music industry is a multi-billion-dollar network with elaborate tours by major artists and vinyl sales reaching new highs. Monmouth doesn’t have a program large enough to keep up with this rapidly growing industry and the BSA should be their opportunity to put us on the map for music students, rather than a place for Springsteen to hold his stuff.”

Similarly, the long-time employee who wished to remain anonymous said, “So much more could have been explained about how this building could serve students and faculty. Will there be symposia held in the building? Will there be research space for collaboration across departments? Instead, it sounded like it’s a garage for Bruce Springsteen’s stuff.” They also added, “I learned about the BSACAM expansion at the end of the employee phone call with President Leahy one day before the big reveal. Honestly, I thought it was going to be something with money for new scholarships. I didn’t expect the big announcement to be this. At the end of the call, the President was like, ‘Does anybody have any questions?’ and nobody had any questions or comments. It was crickets…If nobody has any questions, the truth is, they actually have a million questions and are either afraid to ask or just too dumbfounded and stunned that this is happening.”

In his speech at the BSACAM expansion announcement event that was held on Wednesday, Oct. 18 in the Great Hall on Monmouth campus starting at 11 a.m., Bruce Springsteen said, although with a dose of humor, “I’m glad about getting all of the junk out of my house because it was really getting cluttered in there. Now I got some place to put that stuff.”

Despite the data shared in this article some employees, alumni, students, and faculty question the direction of the university and its fundraising priorities despite the $21 million gift that was announced earlier this year that was raised in support of high-achieving students facing financial hardship, as the single largest donation in the history of the University. President Leahy continues to be optimistic about Monmouth’s future and believes that the University is in good financial standing. “I think the University is in really strong financial shape right now. We remain the envy of other private and public colleges and universities in terms of our financial strength,” he said. “That does not mean we’re not dealing with fewer resources; we are—fewer students, fewer resources to pay for our infrastructure. We’re just working through that as we ramp up fundraising and continue to strengthen the long-term outlook of the University.”

“You students deserve to have continual investment in your University, and that’s my plan while I’m the President here,” President Leahy summarized.